Sunshine State Sources Equipment Maintenance

The State of Florida has long been considered among the nation’s most progressive in introducing innovative and leading-edge practices in modernizing its procurement operations. Florida was one of the first states in the country to introduce e-procurement through its MyFloridaMarketplace tool and one of the early adopters of strategic sourcing.

The state was also one of the first to see its strategic sourcing consulting contracts expire and to implement strategic sourcing on its own without consulting support.

In the October 2006 issue of Government Procurement, the “Sourcing in the States” column asked readers whether states could sustain strategic sourcing after their consultants departed. With their procurement of maintenance management services, Florida’s Department of Management Services (DMS) answered this question with a resounding yes, and again showed that the Sunshine State was at the forefront of innovative government procurement practices.

Maintenance contracts are among the trickiest–and most costly–contracts for chief procurement officers to negotiate. Many products used in an office environment come with a warranty that, for a limited time, covers required maintenance. When those warranties expire, procurement departments often encounter difficulties. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) often tell their customers that only they can maintain and repair the equipment. Many times, these discussions yield sole source contracts at rates far above market prices. DMS aimed to rectify these challenges.

Multiple Agencies, Suppliers, and Service Methods Lead State to Sourcing

In many ways, Florida’s procurement of equipment maintenance management services comes directly from the strategic sourcing playbook. The state’s spend for maintenance was disaggregated across multiple agencies and many suppliers. Neither the purchasing director nor the facilities staff had any visibility into how the state’s equipment was being maintained and at what cost. The method of payment was also inconsistent.

In some cases, the state was paying for maintenance on a time-and-materials basis. More often, state agencies had monthly, quarterly, or annual maintenance contracts where the state paid a flat fee for all work performed during a certain time period.

These maintenance contracts were convenient and easy to manage. Agencies simply had to pay a set amount to cover all of their service needs. There was no need to keep track of the hours worked by a repair technician. The contracts also were abundantly easy to budget. Agency fiscal officers knew ahead of the fiscal year exactly what costs would be incurred to maintain certain pieces of equipment, but the state paid dearly for these conveniences.

There may have been months when the amount of work exceeded the monthly payment of an annual maintenance contract, but not surprisingly, suppliers rarely ended up on the wrong side of the equation. That left one party who did–the state.

Data Dilemma Drives State to Service Management Alternative

From a cost containment standpoint, paying for maintenance on a time-and-materials basis for certain types of equipment is clearly the preferable alternative to a fixed-fee annual maintenance contract.

However, many large organizations do not have the resources on staff to manage an army of technicians and repair personnel. The staffing problem is especially acute in state governments that have been forced to absorb punishing personnel cuts, particularly in administrative positions. Florida recognized this reality. Instead of relying on personnel to manage a myriad of vendor relationships, multiple renewal dates, and scores of pieces of equipment, the state planned to solicit an equipment maintenance management firm that would be responsible for managing maintenance contractors’ service delivery.

Florida understood that for its procurement of equipment maintenance, calculating the state’s spend would be impossible. There was no source data that would detail all or even a majority of the machines that would need to be maintained, nor was there a compendium of the existing contracts in need of transition. The locations of the machines also was an unknown. Gathering the data on tens of thousands of devices would be virtually impossible for precisely the same reason why the state could not manage several thousand time-and-materials contractors–a lack of administrative personnel. The effort may well have taken a full year–staff time that the state simply did not have.

Supplier Sorts Savings and Equipment

According to Charles Covington, Florida’s Director of State Purchasing, government entities typically focus on providing services to the citizens of the state, instead of allocating resources to start new programs, manage projects, and collect the data needed to make enterprise-wide decisions. With this in mind, Florida elected to have the vendor identify opportunities for cost savings and efficiencies.

Florida’s solicitation not only acknowledged this problem, it requested the responders to provide a solution. In the Invitation to Negotiate (ITN), DMS put the responsibility of identifying and tagging pieces of equipment on the winning bidder. Rather than delaying savings by upwards of a year, the state’s solicitation was structured so that savings could begin as soon as eligible equipment was placed on a policy. At the same time, the winning supplier would begin the arduous task of verifying all of the pieces of equipment in scope for the contract and documenting their whereabouts.

Suppliers first got wind of the state’s intentions when it initiated an ITN in June 2003. In the ITN, DMS asked potential bidders to outline their capabilities and to identify the categories of machines that they were capable of servicing. Based on the responses, DMS knew which categories to include in the ITN to guarantee sufficient competition. In order to maximize the volume, and therefore, its leverage with suppliers, the state’s objective was to include as many categories and pieces of equipment as possible.

At the same time, the state did not want an ITN so broad that only one bidder–or worse–no bidder could reasonably bid.

Covington stated that an ITN allowed the state to hear proposals from bidders about their technical capabilities and program management. Subsequently, the state negotiated with an appropriate number of vendors and made its single award decision based on a combination of technical capability, service, and cost–a best value determination.

From the knowledge gleaned in the ITN responses, the state defined the scope of equipment to be covered into four general categories:

Office Automation

- Copiers

- Fax machines

- Scanners

- Computers

- PCs

- Printers

- Monitors

Communications

- Telephones

- Voice mail systems

- Routers

- Hubs

Security

- Security systems

- Surveillance cameras.

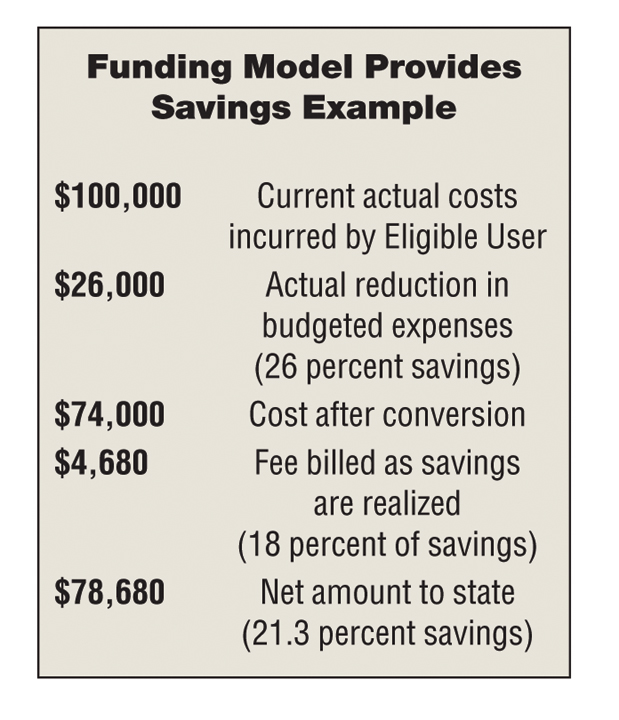

The ITS cost section asked suppliers to commit a specific percentage savings for each of the categories above. The winning supplier, Specialty Underwriters (SU), committed to save the state a minimum of 26 percent across all the categories, compared to the prices previously paid under maintenance contracts.

The state would not have to lay out any funds to pay the winning supplier. Instead, the supplier would be paid 18 percent of the gross savings. SU was to be paid on a quarterly basis as savings accrued during the first three years after equipment came online under the new contract. To make this complex process more tangible, the contract offers an example so that customers know what to expect both in terms of savings and in the funding model.

Without detailed data in the ITN, how was SU able to commit to a 26 percent savings figure? SU Vice President Tim Peterson explained, “Through 25 years of maintaining systems, we have developed a proprietary database that precisely projects a certain amount of savings in a variety of categories.”

Best Value Serves State

While saving money was certainly a primary factor in the state’s decision to engage an equipment maintenance management firm, the ITN was by no means a low-bid solicitation. The equipment that the supplier would be responsible for maintaining is at the core of how a government operates–telephones, computers, and fax machines.

The state did not want a supplier who would offer enormous savings but would either be unable to service machines statewide or would go bankrupt in six months. A firm’s longevity and experience in serving organizations of similar scale were very important criteria in the solicitation. Responders to the ITN were asked to supply three references for engagements that were similar in scope.

After a round of best-and-final offer negotiations, DMS awarded the contract to SU. DMS informed the state agencies that an award had been made and that they would have an opportunity to participate if they so desired.

The Department of Education (DOE) was chosen to prove the concept and demonstrate the program’s value to other agencies. Because the contract was voluntary, it was incumbent upon SU to gain a win to reference while trying to add new agencies and pieces of equipment.

End Users Savor Service

Interestingly, it was not savings but service levels that gained accolades and converts for SU at the DOE. Under its legacy maintenance contracts, the DOE was forced, at times, to endure poor service from vendors who held sole source contracts, and with whom the state had little leverage. However, soon after the DOE began working with SU, the department complained about a vendor who refused to repair equipment in a timely manner. SU was able to replace the existing vendor with an agency-approved firm.

Tim Peterson of SU emphasized that while savings garner most of the attention from a governor’s office, for the end users, the benefits of a maintenance management program are broader than just dollars and cents.

“It’s really not just cost savings; it’s a management program,” said Peterson. “The client realizes that they have options in choosing vendors to maintain their equipment–in most cases–and that those vendors can be replaced if necessary. As a result, quality is expected to improve after a client implements a contract like this.”

Management Contract Saves Time, Solicitation Work, and Money

In addition to the improvements in customer service, the DOE realized significant savings. Since its inception in 2004, the SU contract has saved the department roughly $360,000 on 7,150 pieces of equipment–a savings of more than 27 percent.

Like many strategically sources contracts, Florida’s equipment maintenance management contract yields dramatic soft-dollar, transactional savings. In the same way that a statewide maintenance, repair, and operational supplies (MRO) contract eliminates the need to procure fastener and tools many times a year, the SU contract saves DMS and state agencies from having to process untold numbers of solicitations. This time savings allows the staff to focus on more strategic rather than tactical activities.

Consultative Approach Improves Government Decision Making

Another characteristic typical of strategically sourced contracts is the transformation of the role of the supplier. In non-strategically source contracts, the relationship between buyer and supplier can be rather distant. By law, buyers cannot share much information with prospective bidders so as not to give them a competitive advantage of other firms. Instead, suppliers must wait for a bid to be issued and then respond to it. They are unable to offer advice on how to better construct a solicitation.

The SU contract, in contrast, allows the supplier to offer consultative services to the state. SU staff is able to gauge where a piece of equipment is in its lifecycle and recommend purchasing a replacement rather than “throwing good money after bad” by making continuous repairs on equipment that is past its prime. Unlike the state’s previous system where it was impossible to get a handle on its tangled web of equipment and maintenance contracts, the SU contract offers a wide variety of reports that allow managers to make informed decisions about their equipment. One report shows the savings achieved by every agency or user. Another lists all equipment being serviced by SU, sortable by agency, equipment manufacturer, or type of equipment. Additional reports detail the pieces of equipment that have received an abnormally high number of service calls, as well as those that are due to come off of warranty soon.

The reports help state managers make sound procurement decisions instead of having to make costly emergency purchases when equipment fails unexpectedly.

State Converts Contracts to Savings

Florida’s contract lays out a methodical process that SU must follow in converting the eligible legacy maintenance contracts into the maintenance management program. The first step is a meeting between SU and the agency staff responsible for maintenance. Together they select the pieces of equipment that will be considered. The agency then sends data to SU, including existing maintenance contracts, maintenance history, general ledger and accounts payable information, acquisition dates, and the warranty periods for each item, as well as identifying information such as make and model, location, and serial number.

If the information is unavailable, SU assists in data collection. SU takes the data and populates its proprietary database to provide an accurate baseline.

With the baseline data in hand, SU develops a projection of the savings that can be achieved by converting the legacy contracts. Based on the age of the equipment, as well as usage and the service methods, SU can project how much to commit in savings.

After reviewing the savings projection and SU’s plan to ensure a seamless transition from the maintenance contract to a contract with SU, the agency has the option to approve or reject the change. Once approved, SU works closely with the agency to add the equipment to the contract. When a piece of equipment needs to be repaired, the agency contacts SU, who in turn, notifies the vendor that it needs to make a service call. When work has been completed, the vendor invoices SU, which then makes the payment directly. The state no longer has to pay dozens of vendors, only Specialty Underwriters.

The convenience of vendor consolidation benefits not only invoicing, but also the end user. Rather than remembering the name and phone number of dozens of maintenance suppliers, state employees have only a single toll-free number to call. The number is printed on the asset tag on every piece of equipment.

After the success at the DOE, SU rolled out the contract to additional agencies. Since 2004, eight agencies have begun using the maintenance management contract to improve their customer service, gain visibility into their equipment’s repairs and maintenance, and drive savings. In all, more than 22,000 pieces of equipment have been transitioned to the SU contract, saving Florida taxpayers more than $1.2 million–27 percent less than the cost under the legacy contracts.

With the contract for maintenance management services, Covington and the Florida Department of Management Services solidified their reputation as a leading-edge public procurement organization. In consolidating its supply base from dozens of suppliers to a single firm, the state generated dramatic savings, while improving service levels and giving its agency customers a higher degree of convenience and reporting visibility than ever before.

About the Author

David Yarkin, former Deputy Secretary for Procurement in Pennsylvania’s Department of General Services, is President of Government Sourcing Solutions, LLC. If your government has taken an innovative approach to strategic sourcing, contact Yarkin via e-mail at [email protected].