Records management 1950s style

As urban areas boomed in the 1950s, so did their land records, and managing all of them began to require plenty of space, staff and time. Cities and counties began adopting innovative technologies and organizational methods to store records and make them easy to retrieve.

As urban areas boomed in the 1950s, so did their land records, and managing all of them began to require plenty of space, staff and time. Cities and counties began adopting innovative technologies and organizational methods to store records and make them easy to retrieve.

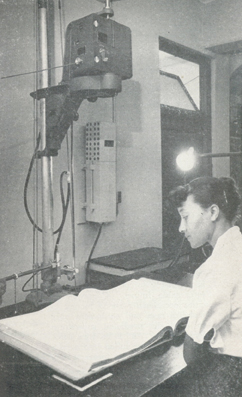

Microfilm became a popular technology among city clerks to preserve records and reduce storage space. The February 1957 edition of The American City featured an account of how Philadelphia condensed records that previously occupied 11,207 square feet to 96 square feet by converting them to microfilm. The records included one book that included a “walking deed” for about 200 square miles executed by Delaware’s Indian tribes for William Penn’s son on August 22, 1737. “The walking deed, common in those days, meant you took ownership of all the property you could walk around in one day….The story is that young Penn had men stationed at intervals around this sizable tract, and they ran the route as a sort of relay.” The deed shows the seals of 24 chiefs affixed in the form of drawings of birds, deer, tomahawks, snakes and crabs. It was one of more than 4 million deeds that would have been recorded on microfilm by the end of 1955, according to the article.

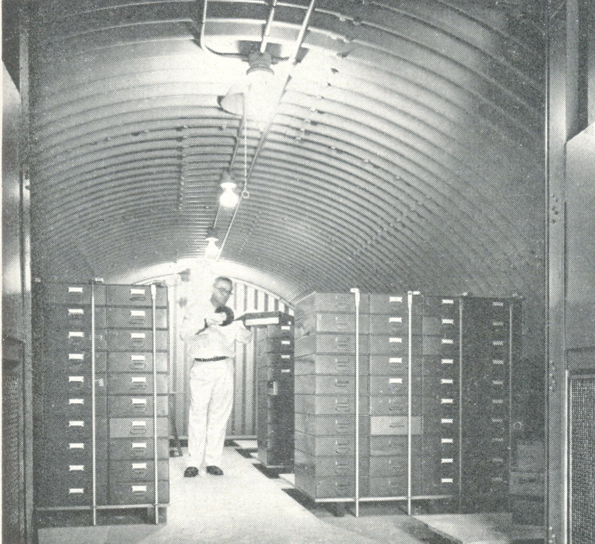

The December 1959 edition of The American City included a detailed description of San Diego County’s record-keeping process under the title, “Winning Back 9,000 Square Feet and Emptying 6,000 File Drawers.” The county used equipment by the Recordak Corp. to take up to 14,000 microfilm shots daily, and it indexed them with a log record and reporting system. “File cards record the work done for each department to date, both by the reel number and by record series. Hence, any clerk needing information on one of the 30 million records or 10,000 film reels can obtain it almost at once. We try to avoid the necessity for cross-indexing and label each file box so clearly that even a new employee can determine which roll is required,” wrote Chief of Records Theodore Reed. The department’s official records were filmed in duplicate, sending one roll to a “back-country vault for disaster protection” and the other to the county assessor for easy access by engineers.

The December 1959 edition of The American City included a detailed description of San Diego County’s record-keeping process under the title, “Winning Back 9,000 Square Feet and Emptying 6,000 File Drawers.” The county used equipment by the Recordak Corp. to take up to 14,000 microfilm shots daily, and it indexed them with a log record and reporting system. “File cards record the work done for each department to date, both by the reel number and by record series. Hence, any clerk needing information on one of the 30 million records or 10,000 film reels can obtain it almost at once. We try to avoid the necessity for cross-indexing and label each file box so clearly that even a new employee can determine which roll is required,” wrote Chief of Records Theodore Reed. The department’s official records were filmed in duplicate, sending one roll to a “back-country vault for disaster protection” and the other to the county assessor for easy access by engineers.