Power to the people

Boulder, Colo., has reignited an infrequent (but still controversial) discussion about public ownership of utilities. Last year, the city’s residents passed a tax to fund a study on buying out its current electricity provider, Xcel Energy. The study concluded that other models are more favorable to the city than Xcel’s in terms of the cost of energy, and the reduction in greenhouse gases and atmospheric admissions.

Xcel’s Regional Vice President Jerome Davis counters the claims, saying the company is the nation’s number one electric utility provider of wind energy and the number five energy provider of solar energy. Davis also says that Xcel provides Boulder residents with electricity at a lower rate than the national average.

Sarah Huntley, a Boulder spokesperson, says the city can aim higher. “It’s very possible and more economical to have a higher level of renewables in our energy mix. If we can achieve that by working with Xcel Energy, the community would be interested in being part of that discussion,” she says.

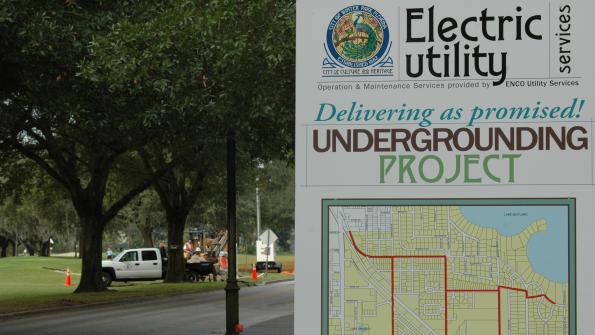

It is not common for a city to take the long and arduous steps required to take over an investor-owned utility. However, successful municipalizations have occurred. Examples include Winter Park, Fla., where a decade ago residents voted to purchase the local assets of Progress Energy.

Since the new city utility was established in 2005, residents have been charged 1.56 percent less for power, says Jerry Warren, director of Winter Park’s new electric department. The System Average Interruption Disruption Index (SAIDI) number — how long it takes for power to come back after an outage — also decreased from 200 to 54 minutes a year after energy became the city’s responsibility, he says.

With more than 100 years of experience in managing an electric utility, Austin, Texas, saw its first rate hike (7 percent) in 18 years in October, 2012. “The increase was because of revenues staying steady while operating costs increased,” says Ed Clark, Austin Energy’s communications director.

Both Austin and Winter Park cite community-wide benefits that result from cities owning their own electric companies. Warren emphasizes the importance of local control. “The citizens are now able to affect decisions on their electricity service,” he says. In Winter Park, that means replacing overhead lines with underground service. Warren also says that when a city owns the utility, the profit otherwise made by a private provider can be used to improve the operation.

In Austin, the city council determines the budget, sets the rates and helps define the strategic direction for the electric company. “Revenues received remain in the community and can be focused to assist other needs,” Clark says. Austin and Winter Park also receive tax breaks as a city utility, which helps lower operating costs.

In an attempt to promote carbon fuels, Austin Energy signed a 20-year agreement in 2008 to buy energy from a woodchip-burning biomass plant in East Texas. The plant doesn’t run “unless the price is comparable to the lowest available prices at the time,” Clark says. He predicts that the plant will be in use once the temperatures warm and the electricity load grows.

But while there are pros to local ownership, there may be more cons, says Rick Bush, editorial director of Transmission & Distribution World, a sister publication to American City & County. For example, Boulder may go through a legal battle to obtain the incumbent utility’s power lines and substations.

In fact, consultants were hired from R.W Beck to conduct a study for Boulder and in its report warned that the city could face strong opposition from the private provider.

“Xcel’s budget to oppose the city’s efforts is effectively unlimited,” the report says. “The city will have to seriously consider whether it wants to engage in a long, costly fight with Xcel to achieve the municipal utility.” In the meantime, Boulder is looking for a third-party consultant to evaluate the financial aspects of the city’s plans.

Ultimately the biggest drive to municipalize in most cities is not the cost of electricity. Rather, it has proven to be about local control, about environmental stewardship and about city citizens having their voice heard, says Bush.

He says that many municipal utilities decide to sell their assets to private companies so that they can tap into the value of their generation, transmission and distribution assets. Most city utilities consider demunicipalizing when the cost to refurbish or replace the local generating station becomes excessively expensive.