The risks of aging infrastructure

By Neil Lieberman

By Neil Lieberman

The water main that broke on July 29, 2014 under Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles highlighted every municipality’s worst nightmare – a piece of old but critical infrastructure failing suddenly and spectacularly. According to the Los Angeles Department of Public Works, the 90-year-old pipe whose rupture flooded the city with twenty million gallons of water “showed extensive corrosion both inside and out and had been welded with a technique no longer in use.” The costs of this damage are still being calculated, but the LA DPW is taking responsibility and will face a bill of budget-busting millions.

The risk posed by aging, critical infrastructure failing suddenly is not unique to Los Angeles. Indeed, many cities and counties are not waiting for a disaster to begin addressing the issue. More and more municipalities are addressing the issue in a proactive fashion by adopting a structured three-step program. The first step is to identify and quantify the areas of highest risk through on-site assessment. The second step is to model different strategies for using limited capital resources to remediate the underlying issues. The final step is to begin implementing what will inevitably be a multi-year remediation effort, including gaining consensus among and approval from multiple constituencies.

Step 1: Visibility

Managing a broad range o f physical assets as well as the entire underground infrastructure that supports the day-to-day operations where there are multiple constituencies can be a challenge, both operationally and politically. Understanding the condition of each asset, its expected remaining life, the likelihood of failure, and the impact of such an outcome is needed in order to quantify the risks and set up an action plan to address them before they become major issues.

f physical assets as well as the entire underground infrastructure that supports the day-to-day operations where there are multiple constituencies can be a challenge, both operationally and politically. Understanding the condition of each asset, its expected remaining life, the likelihood of failure, and the impact of such an outcome is needed in order to quantify the risks and set up an action plan to address them before they become major issues.

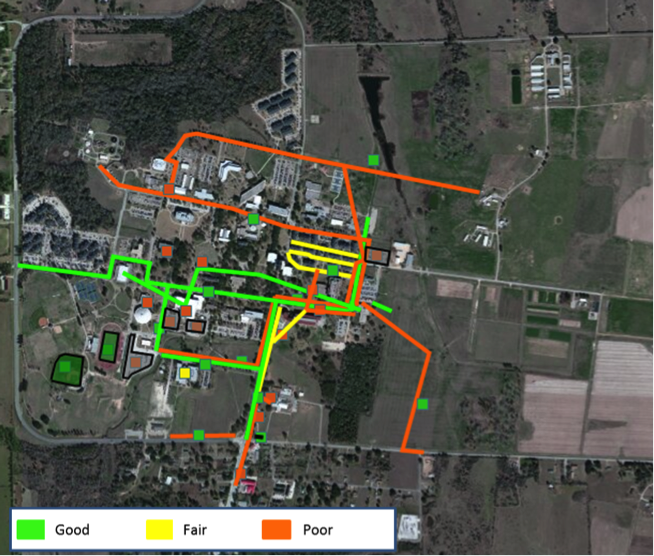

The best practice approach is to start with a thorough review of the entire portfolio through a facility condition assessment (FCA) to understand the condition of each asset, both buildings and linear infrastructure. Regardless of whether assessments are performed by facilities teams or a third party, the resulting condition data is then stored in an accessible central database. Ideally, the data can be viewed on a map that graphically shows both the individual assets and their relationships to each other (see image to the right), which lets facilities teams see the potential impacts of a failure.

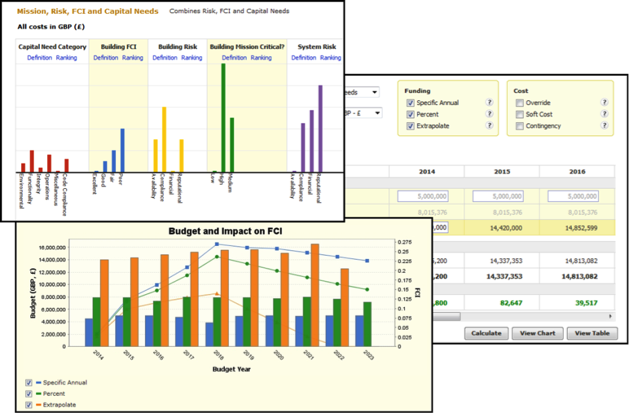

FCAs capture the current condition of each system, along with the costs to remediate any issues and implement end-of-life renewals. From this data, municipalities can calculate the Facility Condition Index (FCI), an objective measure of asset condition derived by dividing the capital needs by the current replacement value of the each asset. This enables sophisticated analysis for decision-making; for example, funding scenarios can show the impact on the FCI over time based on various funding levels.

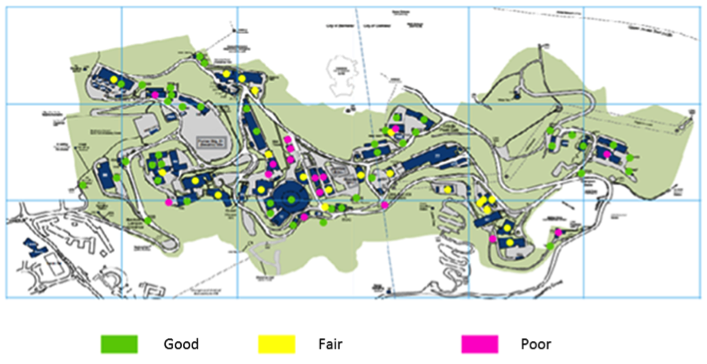

While the condition data from an FCA provides base information, adding a Risk Index provides visibility into where to first focus remediation efforts. For example, investing in a critical water main that is in moderate condition may well be more important than improving a parking garage that is in poor condition. By combining system criticality with an FCI, the relative financial and operational impact of potential failure points becomes clear (see image to the right.)

While the condition data from an FCA provides base information, adding a Risk Index provides visibility into where to first focus remediation efforts. For example, investing in a critical water main that is in moderate condition may well be more important than improving a parking garage that is in poor condition. By combining system criticality with an FCI, the relative financial and operational impact of potential failure points becomes clear (see image to the right.)

Step 2: Prioritization

Identifying potential problems and the associated risks of failure is just the beginning. Prioritizing what to do and when to do it is the vital next step. A data-driven process which evaluates all competing uses of capital based on the institution’s goals and explicitly prioritizes them is highly effective, balancing competing constituencies in an environment of limited resources. Creating and comparing multiple capital “strategies” can often create consensus across different interest groups (see image below).

The strategies defined for ranking capital needs, combined with analytics to understand current status and to adjust as conditions change, create a living capital plan, one that acts as an effective roadmap for addressing capital needs over time.

Step 3: Implementation

Once data-driven priorities have been set, cities and counties can proceed with plans to remediate the most pressing needs. No one can predict the timing of the type of massive failure that affected Los Angeles; however, municipalities can be more prepared as they address aging systems with a high-impact potential.

Conclusion

Cities and counties can’t predict disasters, but knowledge about aging buildings and infrastructure makes it possible to proactively mitigate the risk. Information about both building and linear assets, including data on the current conditions and risks, is a good starting point. Considering the needs of various constituencies, as well as the level of risk, in an objective prioritization process gives municipalities the ability to focus on what needs to be addressed first, and increases the chances of avoiding a catastrophe.

Neil Lieberman is senior vice president and chief marketing officer at VFA, Inc., a provider of end-to-end solutions for facilities capital planning and management.