Financing success

Every year, American City & County receives dozens of nominations for our Crown Communities Awards, and we have a tough time picking our winners. Because there are always interesting elements in each nomination, we decided to highlight them in stories throughout the year. Following are three stories of how several nominees financed their projects.

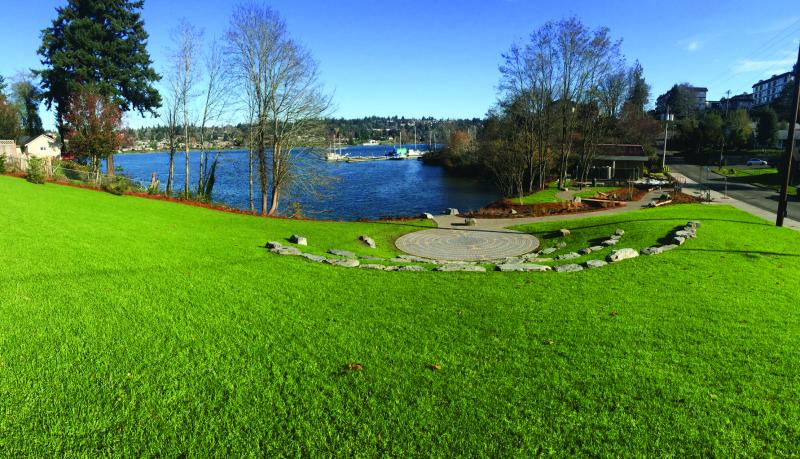

Lillian and James Walker Park Project

Bremerton, Wash. In 2015, Bremerton, near Seattle, completed construction of the Lillian and James Walker Parker Park in an effort to provide the low-income residents of the Anderson Cove neighborhood access to a waterfront community park. The modern green space was named after two icons of the community who spent their lives fighting against racial discrimination in the city following World War II.

In 2015, Bremerton, near Seattle, completed construction of the Lillian and James Walker Parker Park in an effort to provide the low-income residents of the Anderson Cove neighborhood access to a waterfront community park. The modern green space was named after two icons of the community who spent their lives fighting against racial discrimination in the city following World War II.

Based on community interest from a public outreach survey, the city sought to build the new park with features including accessible pathways, beach access, family picnic areas and landscape improvements. The park was also designed to use modern techniques to treat stormwater. Funding for such an ambitious project was no easy task.

The financing eventually came down to a clever use of local, state and federal funding. “The funding was a three-step process,” says, Public Works Director Chal Martin. “First, neighborhood revitalization, second, receiving grant funding to further improve the site with stormwater treatment, and finally, doing the park work itself.”

Approximately $800,000 of funding came from a Washington Department of Ecology grant to implement low-impact development techniques for stormwater control and treatment. These funds were used by the city to purchase the old, beachfront World War II duplex housing units before proceeding to develop the area with stormwater facilities and park features. Some $159,000 came from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for community enhancement.

“We looked for ways to use different grant funding to work together,” Martin says. “This would not have worked if the State Department of Ecology was not flexible. The state department was key.”

With the Department of Ecology working closely with the city’s Public Works and Parks Department, the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the neighborhood itself, the project was completed last November. This community investment resulted in a resource that the city and its residents can pass on to future generations.

Jefferson Barns Community Vitality Center

Westland, Mich.

The Jefferson Barns Community Vitality Center in Westland, part of the city’s historic Norwayne neighborhood, was envisioned to be the linchpin of revitalization in a struggling community. The center was once an abandoned elementary school, but it now serves as a community hub. The renovated facility hosts the Norwayne Boxing Club, a library, athletic courts and a Nankin Transit system stop. Financing for this influential community project was achieved through numerous sources working together for the enrichment of the neighborhood.

The Jefferson Barns Community Vitality Center in Westland, part of the city’s historic Norwayne neighborhood, was envisioned to be the linchpin of revitalization in a struggling community. The center was once an abandoned elementary school, but it now serves as a community hub. The renovated facility hosts the Norwayne Boxing Club, a library, athletic courts and a Nankin Transit system stop. Financing for this influential community project was achieved through numerous sources working together for the enrichment of the neighborhood.

The largest portion of the funding came from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Section 108 Loan program for neighborhood revitalization. The loan will be paid back through developments each year. The center, however, was not only built through government loans.

“All of our partners here have invested their own funds for the project,” says Joanne Campbell, director of the city’s Community Development Department. “Wayne Metropolitan Community Action Agency contributed $75,000, Nankin bus transit for senior citizens and the handicapped invested $45,000, we received a learning center grant for $65,000 to open a computer learning center, and we’re estimating $20,000 in donated labor from Wayne-Westland community schools. Even though it wasn’t a lot of money, the Citizen’s Council also raised $3,000 to make the library.”

Through a combination of city funding, partners’ investments, donated labor, volunteers and repurposed equipment, the project was able to cut costs and involve local residents. Even the neighborhood’s youth took part in the process. “High school students did a lot of the renovations,” Campbell says. “The 11th and 12th graders were brought out and were able to do real work in the community.”

Many of the rooms in the center are used to provide classes, camps, tutoring and counseling for the residents of the neighborhood, but the work isn’t finished yet. The center has received a $75,000 grant from the state of Michigan to build two baseball diamonds and an outdoor basketball court this spring. Financing the center with resources from within the community ensures residents have an active interest in the facility, and it will play a key role in the neighborhood for years to come.

S.T.R.I.V.E. Project

Ulster County, New York Last August marked the opening of the new State University of New York (SUNY) Ulster satellite campus in Kingston, N.Y. The campus was converted from a former elementary school and will provide educational and career opportunities to graduating students of the adjacent high school. This is thanks to the Strategic Taxpayer Relief through Innovative Visions in Education (S.T.R.I.V.E.) Project that aims to make higher education for the low-income residents of Kingston more accessible. S.T.R.I.V.E. was able to secure funds though green infrastructure practices that will be good for the environment and won’t burden taxpayers.

Last August marked the opening of the new State University of New York (SUNY) Ulster satellite campus in Kingston, N.Y. The campus was converted from a former elementary school and will provide educational and career opportunities to graduating students of the adjacent high school. This is thanks to the Strategic Taxpayer Relief through Innovative Visions in Education (S.T.R.I.V.E.) Project that aims to make higher education for the low-income residents of Kingston more accessible. S.T.R.I.V.E. was able to secure funds though green infrastructure practices that will be good for the environment and won’t burden taxpayers.

Financing for this project came from a collaboration of government, private and educational funding. A total of $1,641,450 of serial bonds were issued by Ulster County which will be reimbursed by Ulster County Community College as part of their rent payments for the facility. The project also received several grants, including $439,000 from the Green Innovation Grant Program, which allowed the center to implement green design elements. This included the development of six rain gardens to reduce and clean stormwater run-off and two green walls that cover portions of the outside of the building with ivy. Additionally, the renovated campus received $3,765,450 from SUNY Capital Facilities.

“As you can see, we used some unique funding coordination to achieve our goal,” says Bob Sudlow, Ulster County deputy executive. “I think this reflects the approach demonstrated through this project—a unique concept that was funded in a very creative fashion.”

SUNY Ulster hopes to provide the local neighborhoods with the opportunity for educational advancement while helping the county and its residents save money. Sudlow adds that S.T.R.I.V.E. demonstrates that strategic partnerships can help achieve transformative goals for communities.

_____________

To get connected and stay up-to-date with similar content from American City & County:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Watch us on Youtube