The invisible asset

The average human can only survive about 4 or 5 days without water according to most experts, and the typical American relies almost entirely on their water utility to provide them with this sustenance. But what would happen if the delivery systems that bring water into our homes were rendered non-functional? How long would it take for our modern lives to crumble?

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has been grading 16 categories of America’s infrastructure in a report card every four years since 1998. The last report, which came out in 2017, gave our nation’s drinking water infrastructure a D.

Since water is absolutely vital to our day-to-day lives, why don’t leaders prioritize this? Most experts seem to agree one major factor is that for the most part, water infrastructure is functionally invisible. You don’t see it every day or rely on it to get to work. You simply turn a tap and it’s there. In that sense, it’s different from other categories of infrastructure, and it’s easy to let it slip as a priority because it’s deterioration isn’t apparent.

However, these systems are deteriorating, and if something isn’t done now to turn that trend around, we might wake up in the future to find the taps have run dry.

Finding funding

As with most difficult problems facing local governments, funding is a major challenge. Greg DiLoreto, former ASCE president and current chair of ASCE’s committee on America’s infrastructure says utilities are only generating about a third of the revenue needed to keep drinking water systems safe and up to date. “Overall, as a nation, we’re not charging enough to meet the expenses that were facing in our drinking water infrastructure,” he says. “We need to be charging what it costs to run these systems.”

The funding issue is two-fold, says Randall Roost, principal planner of Water Operations for the Lansing, Mich., Board of Water and Light and former chair of the Michigan Section of the American Water Works Association. First, utilities are under a lot of pressure to keep rates low, and also consumption on a per capita basis is down considerably.

“People don’t use anywhere near as much water today per person as they did 20 years ago,” Roost says. “Our sales are down, but yet we have pressure to make a larger investment in infrastructure. You have to take a double hit on your rates to in order to fund an increasing level of capital investment in a period in time when consumption is declining.”

The reason for the decline is multifaceted. Plumbing codes changed requiring water-conserving appliances to be installed in new homes and facilities, and as older appliances fail, they are replaced by more efficient ones. There’s also the matter of price elasticity. Roost explains that if a utility raises its rates by 10 percent, they won’t see a 10 percent increase in revenue. People will reduce their consumption to keep their bill low. But these increases need to be made.

DiLoreto says increasing rates is essential, but the increases don’t necessarily have to be politically unpopular – not if the public is educated as to why increases are being made. “People don’t lose an election because they increase a [rate], because they support infrastructure,” he says. “It’s a bipartisan issue – it’s not Democrat or Republican. Everyone wants good infrastructure. It’s the fact that you don’t communicate with your customers that becomes an issue.”

When he was working at a water utility, DiLoreto says they increased rates every year for nearly two decades. The reason it wasn’t politically unpopular was because the messaging was clear about where the money was going, and why the increases were important. Roost agrees that communication is the key to solving the funding issue.

“Utilities have done a very poor job of communicating the value of water to their customers,” Roost says. “We’re out-of-sight, out-of-mind. You turn on the tap, the water comes out. You pay your bill every month and you move on. People don’t think about water systems, and they become complacent about the service.”

Roost explains it in this way. If a typical household uses 5,000 gallons of water a month, they’re using a couple hundred gallons of water per day. Water weighs 8.34 pounds per gallon, so that means the average home uses about a ton of water per day. Most communities probably pay about 30 some odd dollars per month, or about a dollar a day for all the water they use.

“Can you name one other commodity that you can purchase, and have a ton of it delivered to your house every day at exactly the time you want it there, meeting all of the standards, for a dollar a day?” Roost asks. “Nobody can deliver anything for a dollar a day, but your water utility does that 24/7, 365 days a year. People don’t think about it that way.”

Aging infrastructure

Because of this lack of awareness, some cities still have segments of their drinking water infrastructure that were put in place during the Civil War. Roost says the oldest water mains in his system were put in in 1885. Obviously, these components have outlived their expected usefulness.

“If I look at my infrastructure simply from an age standpoint I would say those assets probably need to be replaced,” Roost says, but the problem isn’t as simple as replacing the oldest components with newer materials. “The fact of the matter is I have infrastructure that was put in place 50 years ago that may be failing at three or four times the rate of those older assets,” he adds. There are many technical reasons for these types of failures including water chemistry, materials used and construction techniques.

This means there isn’t really a one-size-fits-all solution to the material problems facing the nation’s drinking water infrastructure. Patrick Hogan, president of the Ductile Iron Pipe Research Association, says. Water systems are extremely complex, and a reason for that complexity is that each system is different – with its own unique issues.

Further complicating matters is the fact that the majority of these assets are underground, Roost and DiLoreto say. So, while utilities might have an understanding of the relative age of the components in their system, there’s not yet an efficient, cost-effective way to accurately determine those components’ condition.

Digital asset management

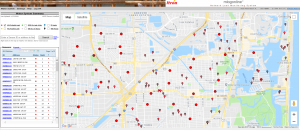

North Miami Beach’s digital asset management tools allow engineers to visualize potential problems in their system.

However, there are tools available that are getting close to this goal. Karim Rossy, a Development Engineer at North Miami Beach Water, says leak detection technology has gotten more sophisticated, leading to improved efficiencies and tremendous cost savings across entire systems.

In the late 80s and early 90s, Rossy was tasked with detecting problems in the system. He would go around with audio sensors, listening through headphones to valves for signs of leaks. Using the data gathered, he’d triangulate where a problem was likely occurring. While this was an important task, physically going valve to valve and listening for leaks is extremely time-consuming and resource draining. “It’s a very tedious process when you have 10,000 valves,” he says.

In the early 2000s, the utility hired an outside consultant to take over the work, but even then, the process was extremely labor intensive. Consultants would come at regular intervals, but would only be able to cover two or three square miles at a time. “We have 25 square miles of infrastructure,” Rossy says. “It would literally take a year and a half to two years to cover the entire system doing it piecemeal like that.”

The solution came when the utility transferred to automated metering systems. During that transition, digital acoustic leak sensors were incorporated into the system – nearly 11,000 of them, Rossy says – which automatically do the work of the technicians who were once charged with physically walking the system, putting their preverbal ear to the valves.

“These sensors listen to the water traveling through the pipes and if a leak develops, it will hear the noise,” Rossy says. The sensors are constantly communicating with the utility through a fixed network, and they alert the engineers when they hear something abnormal. By setting up the network in this way, he says the entire system is under constant watch.

“I’m able to look at the entire network from my office,” Rossy says. “I can see all the sensors and it will show me which are quiet, which are sensing a possible leak, and which are sensing a probable leak.”

This allows Rossy to prioritize his consultants’ time. instead of having them walk the system square mile after square mile, Rossy can hand them a list of probable leak locations, and have them go out into the field to pinpoint the exact source of the problem for repair crews, saving a lot of time, resources and money.

“This past December I gave [the consultant] a list of 72 locations, and he came back with 25 leaks,” Rossy says. “With those 25 leaks, it amounted to an estimated 70 gallons per minute lost, which translates to 100,000 gallons per day, which is 3 million gallons per month, which is 36 million gallons per year.”

The path forward

We didn’t get into this predicament overnight, and the problem won’t be solved overnight, DiLoreto says. However, we need to start working incrementally now to avoid major problems in the future. He encourages local leaders to immediately start planning and prioritizing using the best tools they have available and applying the dollars they have in the most efficient manner they can. This means understanding these complex systems and applying appropriate maintenance where and when it’s needed.

Hogan also says it’s important to hire good people, communicate with them and trust them. Because of the complexities of these systems and the level of expertise necessary to run them effectively, local leaders need to be able to rely on their engineers and consultants to point them in the right direction. When it comes to reinvesting in water infrastructure, “you want to do it right, you want to do it right the first time, and that’s why you need to trust the water professionals on the ground… talk with your utility manager and your engineers and trust their advice. They’re not going to lead you astray.”

Rate increases are going to be unavoidable. DiLoreto suggests preparing customers for that unavoidable fact now. Rather than waiting until it’s an emergency, slowly begin increasing rates now while communicating with the public why rates are increasing and where the money is going. If people can plan for small price increases, they aren’t likely to become as frustrated as they will be if rates are hiked significantly all at once.

Roost encourages utility operators to develop a complete asset management strategy, not only taking into account the age of assets, but also performance metrics. “It’s pretty common for water utilities to simply use age or the number of breaks on a piece of pipe as an indicator of when that pipe needs to be replaced, but they may not be looking at things like hydraulic performance requirements, water quality concerns and location of critical customers,” he says. “These are all of the things that have to go into a well thought out asset management strategy for trying to prioritizing when you should be replacing an asset, repairing it or rehabilitating it.”

This thoughtful approach to managing water infrastructure also applies to other, unrelated agencies as well, Roost says. The most cost-effective way to deal with water projects is to tackle them in conjunction with other work that’s being done. “I can save 20 to 30 percent of the cost of a main replacement by doing it at the same time that they’re going in and rebuilding a roadway,” he says for example. “If we coordinate those activities, all of us save money.”

DiLoreto puts it simply – in order to improve critical infrastructure, you need three things: Strong leadership, increased monetary investment and a willingness to use new ideas and technologies when repairing old components and building new sections. If communities can combine these three elements, America will continue to enjoy clean drinking water on demand for decades to come.