Breaking the cycle

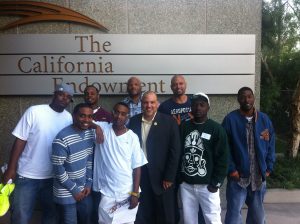

DeVone Boggan (right), Chief Executive Officer of Advance Peace, a non-profit gun-violence reduction program.

Gun violence seems to be an insurmountable problem in America, and this issue is disproportionately concentrated in urban areas – particularly in impoverished and underserved communities of color.

There are different, sometimes conflicting, schools of thought on how to put an end to the carnage, but one thing is for certain – there are no silver-bullet solutions.

One community, however, seems to be making headway. Over the past seven years, Richmond, Calif., has seen a significant decrease in gun-related violence. How did they do it? Well, that depends on who you ask.

In the early 2000s, DeVone Boggan, now the chief executive officer of Advance Peace, a non-profit organization dedicated to combatting gun violence through intervention, was the director of Richmond’s Office of Neighborhood Safety. He was tasked with using non-law enforcement tactics to reduce gun crime in the city. Going by the numbers alone, it seems he was successful. During his tenure, gun violence in the city decreased by orders of magnitude.

Exactly how much Boggan’s work can be credited with reducing the violence in Richmond is hotly debated and his tactics are widely disputed, but the fact remains Richmond did see significant reductions. So significant that other cities plagued by gun violence were willing to give his methods a shot – controversial though they may be.

The proving ground

Above and below: Fellows in Boggan’s program travel to new cities, meet with civic leaders and perform acts of community service instead of participating in lives of crime.

Boggan served for almost a decade as the Director of Richmond’s Office of Neighborhood Safety. It was here that he developed the tactics he now employs in his non-profit gun violence reduction program Advance Peace.

The approach, Boggan admits, ruffled feathers. “We hired as city government employees formerly incarcerated individuals who themselves had gun charges in their backgrounds,” he says. These employees were given the title of “Neighborhood Change Agent,” and they were tasked with engaging members of the community who were at a high risk of participating in gun violence or becoming the victims of it. Each of these Neighborhood Change Agents were from the very communities [to which they were reaching out.]”

Once trained, these change agents would be deployed into volatile communities where they would first establish a highly visible presence and then begin to develop relationships with key players in groups where gun violence was most prevalent. “We asked them to help us… learn about who those individuals were who were driving gun violence,” Boggan says. Typically, these were those who had avoided the reach of law enforcement.

“Most of the guys that we are engaging are thought by law enforcement to be responsible for ongoing, recurring, retaliatory and gun violence, but they had yet to be prosecuted or incarcerated,” Bogan says. “We would engage these very individuals in an effort to neutralize gun violence but also to develop relationships with these guys and connected them to needed resources.”

“Most of the guys that we are engaging are thought by law enforcement to be responsible for ongoing, recurring, retaliatory and gun violence, but they had yet to be prosecuted or incarcerated,” Bogan says. “We would engage these very individuals in an effort to neutralize gun violence but also to develop relationships with these guys and connected them to needed resources.”

As the Office of Neighborhood Safety progressed in its work, it started to find the list of potential clients was actually very small. It was discovered that in Richmond – a city with over 100,000 residents – 28 individuals were thought to be driving 70 percent of gun-related crime, Boggan says.

“We made a decision two years into our work to take our $1.2 million budget and focus it on these individuals,” Boggan says. Prior to this shift, the office was reaching out to approximately 200 people. This change in tactics was a turning point for the organization.

Over an 18-month period, all seven neighborhood change agents were reaching out to these 28 individuals every day, including weekends, multiple times a day. “We felt that intermittent engagement wasn’t enough to neutralize active firearm offenders who had avoided the reach of law enforcement,” Boggan says.

Once trusting relationships were established, agents then sat down with each of these young men – now fellows in the program – to create a personalized life management action plan consisting of a series of goals set for three six-month periods associated with educational, employment, physical, spiritual and mental health opportunities. These individualized goals were crafted in such a way to help these individuals get back on the right path and remain there, Boggan says.

Through this process, the program’s fellows would be connected to a multitude of appropriate support systems, both public and community-based. However, that action came with a caveat, Boggan says. “I learned early on most of these programs were not built or ready to serve this population, nor was this population ready to be served by the traditional apparatus,” he says. “We’d have to go out of our way to identify… programs that could deliver optimal outcomes for this population.”

This is a significant problem, Boggan adds. “Not one of these individuals in our past work or our current work when we began engaging them was being engaged by any public- or community-based system of care other than law enforcement,” he says. “I think that’s an important note – most active firearm offenders who are avoiding criminal consequence are not being engaged by any social service apparatus whether it be a public system or community-based.”

Another opportunity made available to the fellows is what Boggan calls transformative travel. Through this program, trips are facilitated for the fellows throughout the state to meet with community and cultural leaders and icons and to participate do community service and restorative justice exercises. “The point of these excursions is first and foremost to build their horizons. To give them a chance to breathe… they can let their guard down. I want them to like how it feels to not live like they live in their city of origin.”

If these trips take fellows out of the state or out of the country, which happens several times a year, fellows can only participate if they are willing to travel with a rival – someone who they’ve tried to kill or has tried to kill them. “I don’t want to oversell it, there’s no kumbaya moment when they get back to their home cities, but there is an understanding,” Boggan says. “They understand they are the same people, and they often end up liking each other.”

These elements of the fellowship don’t raise many eyebrows, but here’s where it gets complicated. The final element of engagement, Boggan says, is the most controversial in his system. Through the so-called life-map milestone allowance, after six months of achieving goals and abstaining from criminal activity, fellows become eligible to receive a stipend of up to $1,000 per month.

This allowance caused uproar in Richmond and other cities where the model is being adopted through Advance Peace. Headlines to the effect of “Paying Criminals Not to Kill” have popped up, which Boggan says oversimplifies and sensationalizes the actual work being done on the streets.

But just because something is controversial doesn’t mean it’s without merit. What have the results been?

To hear Boggan tell it, his program is a resounding success. In Richmond between 2010 and 2016, the program was offered to 115 suspected active firearm offenders who had avoided the consequences of legal actions and law enforcement, Boggan shares. Over that time period, 84 young men between the ages of 16 and 27 years old accepted the offer. Of those 84 fellows, 94 percent are still alive, 83 percent haven’t been injured by a firearm and 77 percent aren’t a suspect in a new firearm crime.

“What that’s translated to, in the city of Richmond, is a 66-73 percent sustained reduction in gun crimes,” Boggan says. When he started his work, Richmond had recorded 312 firearm-related incidents. At the time AC&C spoke with Boggan, there were 24. “[This] significant reduction has been sustained for the past 7 years,” he says.

This is a bold claim and one of which many – particularly those in law enforcement – are skeptical. Fresno Police Chief Jerry Dyer is one of these skeptics.

In late June, Fresno’s city council voted to approve a 90-day exploratory period to investigate the potential efficacy of partnering with Advance Peace, local media reported. Shortly thereafter, Fresno’s Mayor Lee Brand vetoed the program, citing budgetary constraints. Dyer thought this to be a prudent action.

“I’ve been doing this 18 years as the chief and 40 years in the department,” Dyer says. “I’ve seen a lot of programs [like Advance Peace] come and a lot of programs go, and every time I hear a program say this is the answer, I get a bit squeamish.”

The problem, Dyer says, is that gun violence rates are tied to an overwhelming number of factors – so many factors that it’s nearly impossible to draw a definitive conclusion as to what has or hasn’t directly impacted changes in the numbers.

“The difficulty that I’ve seen is [identifying] the cause and effect,” Dyer says. “There are so many things that contribute to violence and crime. You could have changes in laws, you could have reductions or increases in a police force, you could have different enforcement strategies, you could have a new D.A… there are just so many areas that have to be looked at.”

“When someone says this worked because of “X,” I always look at what else could have caused that,” Dyer adds. “If you could say we did “X” for this amount of money and it directly caused – 100 percent – “Y,” it would be great. But you can’t do that.”

That being said, Dyer says he’s always willing to listen to new ideas and learn about new, innovative methodology that has worked in other communities. He understands that law enforcement is only one cog in the machinery of community safekeeping. With that in mind, he believes that the philosophy of Advance Peace is a great one, but it’s flawed in its tactics.

“Advance Peace targets those individuals who are the most active shooters in a city. It gets them the counseling, the services, whatever it takes to get them to change their lifestyle,” Dyer says. “If I stopped right there, it would be a great thing.”

The bridge too far for Dyer is providing funding to individuals suspected of a crime. “That doesn’t resonate very well with citizens in general who say, ‘why are we rewarding these individuals?’” he says. “That’s what created the controversy in our city.”

Regardless of the controversial methods and ephemeral results, numerous cities have expressed interest in Boggan’s model – 45 to be exact. Boggan says he’s fostering relationships with new cities, and he’s working to sustain the partnerships already established.

While Fresno seems uncertain, Stockton, Calif., and Sacramento, Calif., have both been working the with the program and according to city officials, the results seem promising. Khaalid Muttaqi, director of the Office of Violence Prevention in Sacramento, says that while it’s still far too early to make definitive claims, there are indications the partnership is working.

While he admits there was controversy at first – mainly for the reasons Dyer laid out – the results are silencing many of those concerns. “We’re starting to see some very positive indicators that it’s having an impact already,” he says. “Measurable results aren’t supposed to start for four years, but for example 2018 was the first year in the city of Sacramento that we went an entire year with zero child homicides. That was big for us.” He adds the year before the city’s partnership with Advance Peace, there were nine.

The methodology of Advance Peace and other intervention programs like it might seem unpalatable to some, but even if the results are inflated, it’s difficult to argue they aren’t making progress in the right direction. Which shines a light on a major philosophical question in the American justice system – do we want to punish crime or prevent it?

Intervention versus enforcement

Above and below: The Fresno Police Department is heavily invested in community outreach efforts, not only to build up good will with the community, but to prevent young people from engaging with gangs and participating in criminal activity.

By the very nature of the work, Advance Peace cannot work closely with law enforcement – and this is where similar programs, Boggan says, have fallen short. In order to be effective, a balance has to be struck where both interceder and enforcer can respect each other but keep their distance.

“Our relationship [with law enforcement] is very limited,” Boggan says. “Many in law enforcement are challenged by what we do because of that. We really don’t need anything from law enforcement, but we need them to allow us to do our work.”

And this work, Boggan says, is not something law enforcement is capable of doing.

Dyer, however, takes umbrage to the idea that law enforcement is strictly reactionary. Using new technologies, intelligence gathering and data-driven policing, he says it’s possible to intervene before violence takes place. “I’m a big believer in targeted enforcement,” he says. “That means targeting specific gangs that are the most violent and using your resources to impact their leadership.” By dismantling the structures of these organizations, Dyer believes it’s possible to prevent violence in the first place.

Additionally, Dyer says his department is heavily invested in prevention efforts. “We have a great street outreach program,” he says. “Whenever there’s a shooting, we’ll notify our street outreach workers [made up of former gang members] who will go intervene. They don’t share anything with us – that’s the agreement. They try and prevent the next shooting. The show up at the hospitals, they show up at the funerals, they show up at the scene to find out what’s occurred and try to calm folks down.”

Additionally, Dyer says his department is heavily invested in prevention efforts. “We have a great street outreach program,” he says. “Whenever there’s a shooting, we’ll notify our street outreach workers [made up of former gang members] who will go intervene. They don’t share anything with us – that’s the agreement. They try and prevent the next shooting. The show up at the hospitals, they show up at the funerals, they show up at the scene to find out what’s occurred and try to calm folks down.”

Finally, Dyer thinks there are myriad ways law enforcement plays a role in preventing people from engaging in a life of crime including mentorship programs, after school programs, activity leagues and simply by being a positive presence in the community. “That’s an important thing for law enforcement to do – to be at neighborhood events and to build trust,” he says.

Muttaqi, however, is skeptical of how much impact these efforts can make. He says the populations he works with hold such a mistrust of law enforcement that they’re highly unlikely to participate in any public program, even if law enforcement has nothing to do with it. It’s for this reason that it’s important for intervention efforts to be clearly identified as having nothing to do with police, or the government in general.

“We can’t expect law enforcement to do this type of intervention work,” he says. “It just wouldn’t work. Their job is to keep the community safe, to hold criminals accountable… but we need to respect and give resources to the intervention workers [as well.]”

It’s here that Muttaqi makes a clear delineation between the work of law enforcement and the work of those whose job it is to intercede. “We need to realize that intervention is its own separate lane with its own separate professional approaches, strategies and methodologies,” he says. “We haven’t done that in most cities. In most places it’s prevention and enforcement.”

Boggan agrees that this type of sustained, prolonged intervention is a key piece missing from most communities’ safety strategies. “This approach and others like it add value in this space because it’s a preemptive, ongoing, less intermittent engagement with those who are at the center of violence and the whole approach is designed to keep these individuals from crossing that line,” Boggan says.

Of course, there will be no end to the debate on the philosophical and moral ramifications of programs like Advance Peace. The concepts of justice, compassion, integrity and safety demand this conversation. However, regardless of perspective, it seems most can agree arrest and prosecution don’t have to be the only tactics used in securing safe neighborhoods.