By the people, for the people

Imagine this: your local government’s elected officials and its department heads are determining the annual government budget. It’s business as usual. As funds are allocated, a large sum relative to your local government — say, between tens of thousands of dollars and $2 million — is firmly earmarked for the community to decide, through a defined process, how to use.

Constituents, from pre-teens to senior citizens, will brainstorm and propose projects like installing LED streetlights or renovating a park for the public money to fund. Community volunteers will assess the proposals and eliminate unrealistic ones. Over a multiple week period, your jurisdiction’s constituents will then vote on the vetted projects they believe are most worthy of the public funds. After the vote, the government will immediately enact the winning projects into policy and work to make them a reality.

This scenario isn’t unprecedented — it illustrates a democratic process called participatory budgeting (PB) in action. PB’s core goal is to let community members decide how to spend part of a public budget, according to the Participatory Budgeting Project (PBP), a nonprofit organization that creates and supports PB processes mostly in the U.S. and Canada.

In doing so, PB ensures that governments respond directly to the needs and priorities of their constituents and spend public funds on items that the people actually want, explains Michael Menser, an assistant professor of philosophy and environmental studies at Brooklyn College and a PBP co-founder.

“Participatory budgeting is a way to really empower residents in their communities and to really engage traditionally marginalized residents as well, and to give people real decision-making power,” says Hollie Russon Gilman, a fellow at Columbia University and public policy think tank New America who authored a 2016 book about participatory budgeting.

First implemented in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1989, PBP estimates that the process has since been practiced in 3,000 cities around the world. It can be implemented using the budgets of cities as well as with those of counties, districts, schools or individual agencies.

However, even with its successful track record, turning a large sum of public funds over to the people won’t necessarily be embraced across the board immediately. “The initial pushback you’ll get is, why would we turn over money to the people? It’s the elected [officials’ jobs] to spend this money. Sometimes, we get that,” Menser says.

“Our response is always that, well, isn’t it better to have a relationship with the folks who elected you and actually work with them to do policy, rather than try to be separated from them and hope for the best or just do it in a top-down way,” he adds.

Most cities in the U.S. carry out PB in the same general five-phase process, Menser says. PBP defines the steps as, design the process, brainstorm ideas, develop proposals, vote and fund winning projects.

Two cities on opposite ends of the U.S. that implemented PB in their communities — Seattle in 2015 and Durham, N.C. in 2018 — found multiple benefits in doing so.

“With participatory budgeting, PB, it really humanizes the budget process,” Durham Budget Engagement Manager Andrew Holland says. “With our process, that’s what we witnessed. A lot of our residents were energized… they really felt as though they had a voice in the process.”

Designing the process

Durham adopted participatory budgeting in May 2018 with a budget of $2.4 million, Holland says. The Durham City council appointed a 15-member steering committee for PB in the city and hired a team including Holland to oversee the process. The city also hired a consultant from Our City, Our Voice in designing a PB process to fit Durham.

Seattle first launched PB in 2015 just for its youth programming, according to the city’s website. However, the city opened PB up to all Seattle residents in 2017 for them to decide specifically how to spend part of the city’s budget on small-scale street and park improvements. Seattle residents are able to vote until Sept. 30 on how to spend $2 million of Seattle’s 2019 budget.

Seattle took a different approach than Durham in designing its PB process. The city contracted with PBP in 2015 to set up its PB process. However, officials also went to community groups and paid community members to function as consultants that participated in open discussions and ultimately helped city staff develop Seattle’s PB format. This “took the city out of the driver’s seat,” explains Seattle Department of Neighborhoods Director Andrés Mantilla.

The relationships Seattle forged during this process would later help it during the voting phase, as these community groups legitimized PB to community members who voted on projects, Mantilla says.

Brainstorming ideas

Like city staff did when designing the PB process, Seattle’s modus operandi when outreaching PB in general has been for the city to go to people about PB rather than have them come to the government.

Seattle has used pop-ups at different events and its community liaison program to outreach PB, says Shaquan Smith, Seattle’s participatory budgeting coordinator. However, libraries heavily distribute information throughout branches in Seattle, too.

When ideas are collected in Seattle around January and February, residents can submit their ideas at pop-up events, at libraries or through Seattle’s online PB platform, Smith says. A particular focus this year has been given to gathering more input from communities of color and for bringing more focus to equitable areas. However, outreach is a challenge in a city of almost 800,000, Mantilla says.

Durham’s PB team compiled a list of community stakeholders and nonprofit organizations, and enlisted them to help get the word out about PB and its benefits, according to Holland. The team also went to various community meetings, festivals, local schools and religious institutions to educate people about PB.

However, Holland cites education as a major challenge. “At times, it took a while to get folks in the mind frame or the mindset of, ‘hey, you have a chance to decide how to spend $2.4 million.’”

A major focus of Durham’s PB campaign was targeting the poor, marginalized and underserved communities, according to Holland. The city used a third-party vendor and various data sets to target outreach strategies to these underserved communities to ensure that they had a voice in the process. Even undocumented immigrants could participate, and Holland says that a good amount of minorities both submitted project ideas and voted.

During this phase of Durham’s 2018 PB cycle, over 500 project ideas were generated. Not all were feasible, so they had to be vetted for the PB vote.

To accomplish this, Durham officials turned again to the community.

Developing proposals

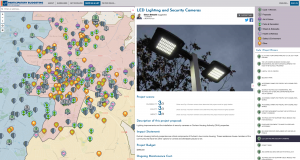

An interactive map showing the locations and types of projects proposed in Durham’s PB process, along with detailed descriptions of those projects and information on how to get involved.

“With participatory budgeting, we want to ensure that residents are constantly part of the process. So, that’s why we wanted to allow the residents to volunteer to work with city staff to vet those ideas,” Holland explains.

Ultimately, around 100 resident volunteers served as “budget delegates” in Durham who spent a few hours each week vetting projects based on equity, impact and feasibility. City staff worked with the delegates to help them determine feasibility, Holland says.

As ideas are submitted in Seattle, the city’s department of transportation and parks department determine the feasibility of each idea and then give the realistic ideas back to the community for what Smith calls the project development phase, he says. This year, about 600 ideas were submitted in Seattle, with about 300 ideas making it to the project development phase.

In the current PB cycle, city staff set up community meeting groups to have residents discuss which of the feasible project ideas that were part of their district were of the highest priority, Smith says. Community members were able to submit feedback on project idea priority through the city’s online PB platform as well. City staff had residents rank between eight and 10 projects in their districts based on need and equity.

“It’s really been a great opportunity to get that first initial access and entry way for a community to realize they have a say in what happens in their neighborhood, and kind of give that power back to them,” Smith says.

After the city’s department of transportation and parks department conduct a final review of the ranked projects, the city then submits the winning projects to the ballot for a vote.

Voting on and funding projects

Smith says that PB can be, “a way for people who may not be used to the voting process, who may not vote on a regular basis, it could be an entry way for them to have an opportunity to vote, especially for the youth as well.” After all, in Seattle’s PB process, community members as young as 11 can participate.

“I think PB is a great way to show young people a lot of different civic skills such as group discussions, dialogue, compromises, learning about how the sausage is really made [regarding] city policy. It’s sort of a hands-on civics education in a lot of ways,” Russon Gilman says.

Delivery of the winning projects can be tough, though.

“We’re trying to move a bureaucracy. And so, getting timely project development back from the departments with full consideration of project impacts and all that is a challenge at times,” Mantilla says, noting the need for working across departments to make it a seamless process.

Durham residents ages 13 and up voted on the projects during this past May, Holland says. Residents were able to vote either on paper ballots or online through the free-to-use, open-source Stanford Participatory Budgeting Platform developed by Stanford University.

Over 10,000 people voted, and Holland considers Durham’s maiden PB flight “extremely successful.”

Now, the city is focused on implementing the project ideas — Durham has promised to implement 50 percent of the winning PB projects within the first year of implementation, Holland says.

But that doesn’t mean that citizen engagement with the PB process has stopped.

“Even today, I receive phone calls and emails… [asking] about, ‘hey, when will my project be implemented in my community?’ That is, to me, one of the most remarkable and most encouraging things that I’ve witnessed, is knowing that you have a good number of residents who are continuing on following us and the progress thus far,” Holland says.

Thinking beyond budgets

Holland’s point underscores a major benefit of PB: it changes a government’s relationship with its people.

“Creating opportunities for folks to get on the same side of the table builds rapport and support,” PBP Co-Executive Director Shari Davis says. “And I think that PB is part of the answer here, but I think one of the challenges in moving PB forward is making sure that folks are on the same side of the table so this is not just another top-down mandate or an example of folks doing intense advocacy not being heard.”

While PB empowers residents in the budgeting process, it yields benefits outside of finance, too. Designing projects and services to tackle complex issues like growing economic inequality, climate change and resilience requires a regular dialogue between a government and its public, so that the government can truly know what they know, Menser says. PB can help strengthen this dialogue and thus allow a government and its constituents to collaborate on solving these complex issues together.

“It brings together the public, the elected [officials] and the city government workers. All three,” Menser explains. “Another way to think about it is that it brings together the government, the community and the expertise: the people who actually understand the technical difficulties of an energy system or of a water system or of a transportation system.”

“With the complex things that cities are trying to solve like around transportation, or around flooding, you need everybody,” he adds.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly omitted Seattle’s 2015 contract with the Participatory Budgeting Project (PBP) to help the city set up its PB process. The story has been corrected to reflect that Seattle set up its PB process by contracting with PBP in addition to working with community members.