Anti-noise advocates call for quieter cities

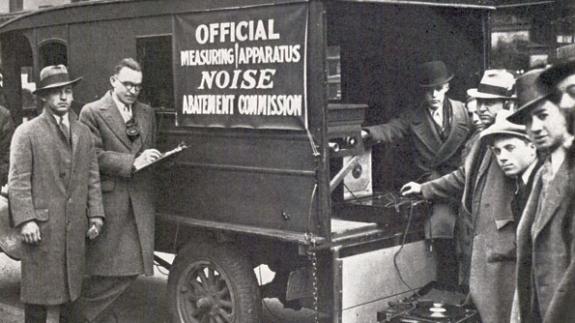

Inescapable, loud, constant noise — it was one of the many problems city officials had to address in the early 1900s, and one that had many vocal opponents willing to fight for peace and quiet. “‘Tintinnabulation, bombilation, vociferation; shriek, clatter, jangle, whine, jar, roar, cacophony,’ — the dictionary words fail to portray the synthesis of sounds that assail the ears of city dwellers during the day and far into the night,” wrote Lewis H. Brown, Chairman of New York’s Noise Abatement Commission (NAC) in the February 1931 edition of The American City.

Inescapable, loud, constant noise — it was one of the many problems city officials had to address in the early 1900s, and one that had many vocal opponents willing to fight for peace and quiet. “‘Tintinnabulation, bombilation, vociferation; shriek, clatter, jangle, whine, jar, roar, cacophony,’ — the dictionary words fail to portray the synthesis of sounds that assail the ears of city dwellers during the day and far into the night,” wrote Lewis H. Brown, Chairman of New York’s Noise Abatement Commission (NAC) in the February 1931 edition of The American City.

The NAC formed teams to carry out its work, including the Committee on Noise Measurement and Survey, the Committee on the Effect of Noise on Human Beings, the Committee on Building Code and Construction, and the Committee on Practical Remedies. They gathered noise level readings on city streets and inside buildings, and scholarly and scientific reports about the effects of noise on concentration and productivity. They also recommended changes in mechanical design and construction practices; proposed new ordinances, enforcement powers and public education; and sought the cooperation of manufacturers to silence the bells and gongs on their products, and of residents to turn down the volume on their activities. By October 1935, the League for Less Noise had formed to ratchet up New York’s efforts, and a report in The American City bragged that in three months it had succeeded in making residents more “noise conscious.”

The NAC formed teams to carry out its work, including the Committee on Noise Measurement and Survey, the Committee on the Effect of Noise on Human Beings, the Committee on Building Code and Construction, and the Committee on Practical Remedies. They gathered noise level readings on city streets and inside buildings, and scholarly and scientific reports about the effects of noise on concentration and productivity. They also recommended changes in mechanical design and construction practices; proposed new ordinances, enforcement powers and public education; and sought the cooperation of manufacturers to silence the bells and gongs on their products, and of residents to turn down the volume on their activities. By October 1935, the League for Less Noise had formed to ratchet up New York’s efforts, and a report in The American City bragged that in three months it had succeeded in making residents more “noise conscious.”

In April 1935, The American City reported that Dr. Orestes H. Caldwell, a director of the American League for Noise Abatement, predicted that the movement for noise abatement would create noiseproofed and noiseless cities in the future. To document the extent of the problem, he said that noise recordings had been sealed into a cornerstone in a New York building, “So that our posterity of the happy noiseless future will be able to get some idea of the continuous torture undergone by their city-dwelling forefathers.” The recordings of traffic sounds, newsboys’ shouts, automobile honks and shoe-leather squeaks were stored on “an imperishable medium,” sealed into a bronze casket, and placed in a cornerstone along with instructions and platinum needles to play the sounds. Unfortunately, the location of the cornerstone was not included in the article.