Improving the competitiveness of U.S. smart cities and counties

In my last article in this journal, “Building smart cities and counties with the Infrastructure Act,” I recommended that the funding available from the Infrastructure Act presented an opportunity for U.S. city and county jurisdictions to ramp up their smart city/smart county programs. At that time I noted that historically the U.S. lags far behind the rest of the world in the rankings and the infusion of federal funding could help the U.S. to catch up with jurisdictions internationally. Sadly, a recent analysis of smart city rankings from a variety of sources shows that the U.S. is lagging even further behind than we were a year ago. The most recent rankings released—the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) rankings for 2023—proves the point. Some of the more salient, and sobering, findings from this report were:

- No U.S. cities were ranked in the top 20 worldwide

- Only four U.S. cities made it into the top 50

- The average rank of U.S. cities was 56.6, with a range of 21-93

- Every U.S. city fell in the rankings, on average by 12.5 places, with a range of 2-19 places dropped

- 14 new cities, none from the U.S., made their entry into the list for the first time

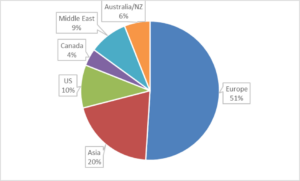

The IMD rankings are consistent with those published by other organizations. While individual rankings may be better or worse when evaluated under different methodologies, the conclusion remains the same—the U.S. is rapidly falling behind while Europe and Asia, in particular, are threatening to lap the field. Figure 1 shows the share of top IMD 100 rankings by region.

(Source: author’s analysis of IMD data)

As information and communications technology (ICT) is a primary enabler of smart cities and counties, it is somewhat inexplicable that the nation that invented the Internet, among numerous other enabling technologies and solutions, should be falling so far behind. Clearly, we have some work to do. Based on my experience with multiple smart city projects in SE Asia, there are some steps that U.S. cities and counties can take to close the gap and begin improving our rankings instead of losing places.

Organize internally

A city-wide or county-wide focus is an absolute must for a successful program. While the chief information officer (CIO) often plays a leading role in smart city/county programs, the CIO does not have the responsibility of defining government-wide non-ICT goals and also lacks the authority to convene and oversee a multi-agency initiative on his/her own. The senior executive of the city/county must not only be supportive of the initiative but be prescriptive to stakeholders across the organization that they will play a role.

Create a governance structure

The internal organization needs to be defined in a formal governance structure. We recommend to all our clients that a smart city/county steering committee be chartered under the aegis of the mayor, city/county manager, or similar senior executive. The governance body is crucial in aligning efforts across multiple agencies, serving as a clearinghouse for related projects, and ensuring that a story is told that knits together what may appear to be disparate efforts into a coherent smart city/county program.

Develop your vision

The first goal of the governance team is to develop the vision. There is no single smart city/county vision. Further, no jurisdiction could possibly execute the myriad possibilities that could conceivably fall into a smart city/county vision. Jurisdictions should define their unique vision by addressing their own circumstances, needs and capabilities.

Develop a plan that links to broader goals and values

As always, ICT is the enabler for accomplishing goals, not an end unto itself. While it is a given that any smart city/county will look to leverage ICT to enhance government service delivery, an exemplary smart city/county plan will address greater goals for the jurisdiction. A notable trend in recent years is leveraging the smart city/county approach to support sustainability goals. Other goals such as digital equity, equal opportunity, citizen engagement, and building communities can, and should, also be supported if appropriate to your vision.

Engage externally

Often key stakeholders and facilitators will exist outside of the government structure. Depending on location, these external stakeholders may include water and electric utilities, regional authorities such as transportation agencies, and other state, or even federal stakeholders. Building partnerships with external stakeholders can be critical to success. While they may not strictly fall under the governance plan from a command-and-control perspective, they can provide valuable support in executing the plan and delivering on the vision.

Leverage what you’re already doing

It is likely that there are relevant projects and programs already underway in the jurisdiction that have not been categorized as smart city/county projects. Next-Generation 9-1-1, intelligent transportation systems, digital equity programs and the like can all play a strong part in the overall program. These should be identified and be part of the overarching smart city/county framework.

Tell your story

Last, but in no way least, is the need to let the world know what you are doing. A little bit of soft marketing can go a long way in raising your profile—and your rankings when the 2024 assessments are published!

U.S. cities and counties can improve their smart city/county competitiveness when measured against international jurisdictions by taking a few simple, steps. With effective smart city/county leadership, organization, and governance jurisdictions can both deliver for their citizens as well as reap recognition on the international stage.

Mike Hernon ( [email protected] ) is the principal of the Public Sector Partnership and director of smart cities for Winbourne Consulting Inc. He previously served as the chief information officer for the city of Boston.