A budding recovery

A budding recovery

Since its 2008 budget year, the revenue line in Atlanta has fallen nearly $120 million, from $645 million to a projected $526 million in its 2013 budget. The reduced income has forced city leaders to make painful cuts in services, furlough and lay off workers and change how the government does business.

But starting in the 2014 budget, revenues reverse course, with a chart projecting future budgets showing a steady increase, rising to $553 million by the 2017 budget year. A modest increase, but welcome nonetheless.

“We think this is the bottom,” J. Anthony Beard, the city’s chief financial officer, recently told a group of financial professionals and journalists. “In Fiscal Years 14 and 15, we see a strengthening in revenue.”

Atlanta is not alone in seeing glimmers of a turnaround in the finances of the nation’s local governments, after one of the most trying periods since the Great Depression of the 1930s. With the economy slowly moving ahead and a tentative firming in the real estate market, financial prospects are brightening, though tempered.

“We’re cautious about what the coming months hold,” says Christopher Hoene, director for research and innovation at the Washington-based National League of Cities and co-author of a September report on the fiscal condition of the nation’s cities. “We think the peak of the cutting was in 2011 and 2012. We hope that is so, but we’re watching from month to month.”

Left to its natural course, a growing economy, though struggling, might be sufficient to lift the revenue lines in local government. But the uncertainty in federal policy making, with looming tax increases and sharp revenue cuts, gives forecasters pause. “We can’t afford another hit,” Hoene warns. “The recovery could easily be turned in the other direction.”

Squeezed by lingering problems

Other experts in local government finance are also concerned about lingering problems related to promised, but unfunded, pension and retirement health care benefits, as well as recent efforts at the state level to reduce their own costs, often at the expense of local government support. Experts also point out that any real estate recovery is uneven and vulnerable, though recent easing of monetary policy by the U.S. Federal Reserve is aimed directly at improving that market.

Other experts in local government finance are also concerned about lingering problems related to promised, but unfunded, pension and retirement health care benefits, as well as recent efforts at the state level to reduce their own costs, often at the expense of local government support. Experts also point out that any real estate recovery is uneven and vulnerable, though recent easing of monetary policy by the U.S. Federal Reserve is aimed directly at improving that market.

“We hope the worst is behind us,” says Robert Zahrardnik, a lead author of the Pew Charitable Trust’s report on local finances, released this summer. “But there’s a lot of room for caution as we move forward.”

Entitled “The Local Squeeze,” the Pew report, from its American Cities Project, says that recent years have been particularly difficult for local government as their traditional pillars of revenue – state aid and property tax assessments – were simultaneously cut from beneath them.

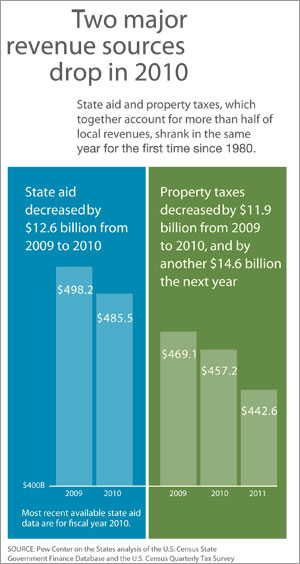

State aid, which funds nearly one-third of local government budgets, fell by $12.6 billion, or 2.6 percent, in fiscal year 2010, according to Pew. That trend is continuing, with 26 states reporting cuts in local government funding in 2011 and 18 states so far in 2012.

Property taxes — the other side of the squeeze — are shrinking, too, Pew found. Those taxes, which amount to 29 percent of local government revenues, have dropped after the collapse of real estate prices during the recession. In 2010, according to the report, property tax revenues were $11.9 billion or 2.5 percent lower than the year before, the largest decline in decades. Property taxes also fell in 2011 and are expected to decrease further in 2012 and 2013, as assessments, which often lag actual property values, catch up to the real estate bust.